This sermon on Ruth 1:1-17 and Mark 3:33-35 was preached at Christ Lutheran Church (Fredericksburg, VA) on the Twentieth Sunday after Pentecost, October 15, 2023. You can also find a recording of this post at my 2 Penny Blog Podcast.

Mother-in-laws can get a bad rap. True, sometimes their relationships with their son or daughter-in-laws may be difficult, and mother-in-law jokes abound, yet they can be a gift. I’m fortunate that my own mother-in-law has always supported and encouraged me even if my own mother did not at times. Now, she’s not afraid to challenge me, but she always does so with dignity, love, and grace. So, I feel very blessed. That is why I often introduce her as my favorite mother-in-law (she’s my only one), and I jokingly tell people I am her favorite son-in-law. This doesn’t always go over big with my brother-in-laws in Pennsylvania and Ohio, but she reminds me that I am her favorite son-in-law in Virginia. She loves and appreciates each of us as if we are all her favorite one.

Surely, defining and understanding family and tribal relationships is not always easy. Getting along with others never truly is. And so, Jesus often uses familial language in very broad terms. He encourages his disciples to think of one another as brothers and sisters…siblings of God. And on the cross, he turns to a beloved disciple and his mother, and gifts them to one another: “Woman, behold your son!” Then He said to the disciple, “Behold your mother!” (see John 19:25-29). He does not want his widowed mother to be alone. It is a very moving scene. His teachings stretch the common understanding of the time surrounding tribe and family.

In indigenous, tribal populations, adoption was and remains common. There were mechanisms and rituals to adopt people into the tribe and family, and in some cases, a murderer might even be adopted into a family to replace the son or daughter who had died. Tribes throughout the earth often had mechanisms to create extended or what scholars might call “fictive family.” It was good for society and individuals to have connection. This broad idea of family reaches from ancient tribal times into Jesus’ world, and into our own time. This practice crosses cultures, including Jewish culture, although with varied rules. I’d wager many of us here today are god-parents or “aunties” or “uncles” to people of which we have no blood relationship. I have twenty-three people who love me as their uncle and call me that – eight of which have no blood relationship. When it comes down to it, what defines family is not laws, culture, or social practices. It rests on a decision to love another person as family. That’s it. We choose to love.

Sure, family is important sociologically. Tribal and national identities in their best sense may serve to unite and protect us. Yet, in our DNA, perhaps reflecting the realities of a fallen world, some genetic and sociological studies suggest that even infants are designed to inherently trust those who look like them more than those who don’t, and this might extend into adulthood.[i] If these studies prove true, some suggest this could reflect an instinct for tribal relationships built into our survival skills. Outsiders (those who look different) rightly or wrongly can be viewed as a potential threat (outside the “tribe”). Certainly, sociological impacts and experiences can influence this too, fermenting racism and other forms of hatred. Sin can play upon our human nature – magnifying it negatively even when some traits might have been implanted in us to help protect us in a dangerous world.

Upon reflection, we see a tension here. There might be an instinctual, fallen tug on us to limit who we see as neighbors or family, but God wants more for us. We can be tempted to dehumanize those who are against us, but Jesus teaches us another way. All the while, God pulls us toward reconciliation and trust – if not unity. That’s God’s promised goal. And yet, the ancient Israelites often interpreted the Ten Commandments application quite tribally. You shall not steal, or murder, or covet another’s property unless perhaps it was someone in a non-Israelite tribe. This ethical construct proved true among many indigenous populations too, including Native American tribes. It wasn’t unique. It was conventional thought.

A lot of this tribal thinking had to do with interpretation, context, and understanding. Familial and tribal relationships were seen through the lens of a dangerous world, and so although exceptions were made, these boundaries tended to be quite strong. Yet if you look deeper at the Mosaic Law, the call was always there for kindness to the foreigners, poor and outcasts among the Israelites. Despite this, in Jesus’ time, outsiders could still be looked upon and treated as an “other” – there were some people with less rights socially, or they became someone yoiu should distance oneself from in order to maintain religious purity, safety, or help ensure cultural, political or personal survival.

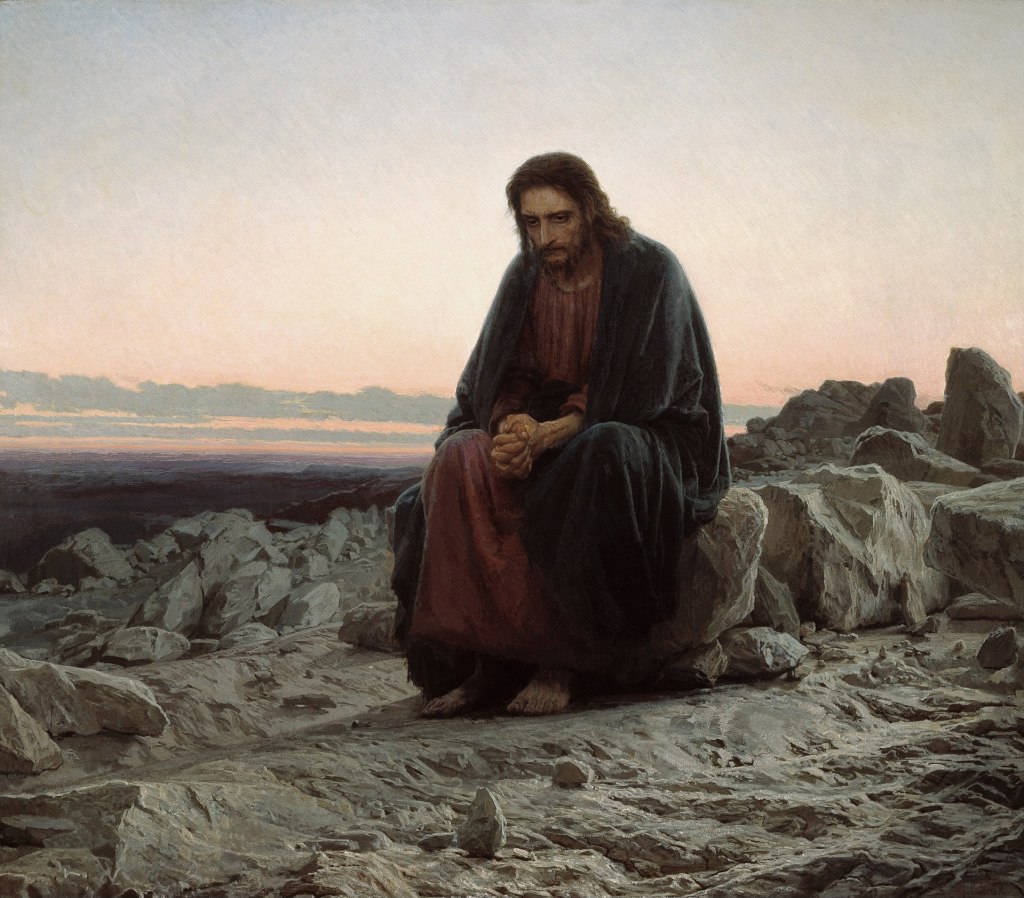

In response, Jesus stretches this human understanding toward the divine’s own. He ate with outsiders. He forgave serious sinners. Heroes in his stories could be from the hated Samaritans or Canaanites. When asked about the identity of our neighbors so that we could love them, Jesus interpreted this in the most open way possible. He taught neighbors were anyone around us, regardless of their ethnic, religious, or socio-economic status. When asked who his followers should treat like siblings, an even closer social status, Jesus answers, “Whoever does God’s will is my brother and sister and mother.” Again…not just someone who believes exactly as I do, but those who do God’s will are our siblings.

In life, relationships are complicated, and few families don’t experience discord over politics, inheritance, or even who loves who more at times. Families remain necessary in a difficult world, but they can have issues. These past years and days sadly remind us that nations can be necessary due to very real dangers. And yet, as a fallen humanity, we don’t always love God or our neighbors as God intended. In return, some family members or neighbors can mean us harm or become toxic to us. Despite our best efforts, ancient tribal animosities may rise within us, and wars might start causing people to argue over who started what…and thus we hurt innocents all along our way.

True, God never called us to be doormats. Sometimes, to turn the other cheek means we turn and walk away. Yet at other times, many Christian theologians (those not explicitly pacisfist) tend to argue that force might be necessary at times – the most limited force possible with the least number of innocents lost…yet force, nonetheless. In any war, even the best of wars, innocents will die. As a former police officer and soldier trained to use force, with friends and acquaintances who have used lethal force, I know that such force can leave a mark on a person’s soul. Moral injury (which is when one feels they have acted outside their conscience or moral compass) is real. I deal with that at times counseling others as a chaplain. And our Orthodox siblings even invite soldiers to confess as a healing medicine no matter how just a conflict. They do so because the best of wars is interwoven with the stain of human sin – always. Our brother’s blood can be heard crying out to us from the ground, like a voice calling for revenge, as it did when Caine killed Able (Gen. 4:10). There is just something inherently wrong with war and killing people even when necessary in a fallen, messed up, dangerous world. It is never God’s hope for us, our families, or the world.

And so, wars may come whether we wish it or not. Violence might visit our household at any time, because people can be overcome by sin and do evil things toward us and the one’s entrusted to our care. We, too, can err. Yet as we seek to discern our own call in response to the realities around us, whether pacifist or warrior or somewhere in between, Jesus’ perhaps hardest challenge to human reason remains. How can we best love even our enemy?

This past week, I have had many ask my opinion on the recent, horrific terrorism and resulting conflict in Israel. I don’t know the full answer. Perhaps, I don’t really have any answers in a situation that is embedded in centuries of ethnic, political, and religious struggles. Yet, I do know that terrorism, racism, antisemitism, and any calls for genocide or war crimes must be clearly and unequivocally condemned…always. Facing this, we are to seek to love everyone – especially the most vulnerable among us – and always pray for our enemies. From the Mosaic Laws, prophetic teachings, and Jesus’ own words, we are seek to show mercy even as we strive for justice…even when fighting for life and death.

So, as the Lutheran World Federation has done, we can urge all sides to value the innocent, respect life, and uphold international law.[ii] For when all is said and done, Jesus was sent to offer salvation for all people, and the Lord intends to bring all peoples to himself. Some might reject Jesus…some might hate us…try to hurt or kill us…but forgiveness, mercy, and love are Christ’s work among us even now…This is God’s will that is trying to work through us. Yet, it remains a tough go…it can seem an impossibility.

And so perhaps it is a gift that the Narrative Lectionary draws our eyes to the very ancient story of Ruth and its possibilities this day. The story is from the time when Judges ruled the Jewish tribes. (Judges, you might recall, were like chieftains of the Jewish tribes before the monarchy. Some were prophetic and spiritual, and some were great warriors just as with the Lakota I worked and lived with.) Those days were a chaotic time. The Tribes were free from slavery. They were finally in the Promised Land, but they were not always good to one another. Also, enemies still abounded because they had not fully defeated the resident tribes as God ordered. Despite the direct commands of God (the Ten Commandments) and all that Moses had taught in his law applying those commandments, people still flirted with foreign gods and did not love their neighbor. And so, the Book of Judges tells us that it was a morally questionable time, “In those days,” it says, “there was no king in Israel.” (One might also argue that God was not even appropriately king of their lives.) And it goes on, “Everyone did what was right in his own eyes” (Judges 21:25).

And yet in the face of this reality, we have this mother-in-law and daughter-in-law lifted up to us for our examination. They are of different tribes (Jewish and Moabite), and despite this, they boldly hold onto one another in love as family. Our Jewish siblings often read this story on the Feast of Shavuot (also known as Pentecost, celebrated fifty days after Passover). It is a time when they remember the gift of the Law (the Ten Commandments) given to Moses. (We Christians tend to remember the gift of the Spirit arriving on Pentecost.)

For her part, Ruth, the non-Jew, receives and accepts God as her God and in effect promises to live by the Torah – receives the Law as her own. The promises of God thus become her gift as well through faith. In another parallel with the feast, the story happens during the harvest, and the feast gives thanks to God for God’s bounty. It is an ancient and surprising story thought to originate in the Judges period and was orally transmitted until written down after the Babylon exile had ended. (I’d encourage you to read the complete story at home this week. It is short, but very engaging and informative.)

Ruth’s name means “compassionate friend,” and as is often the case with ancient tribal names, she is just that. Naomi had married a Moabite, as had her now deceased son, and that’s how Ruth and she came into relationship despite being from different peoples. Naomi wanted to accept her fate among her Jewish people. For her part, Ruth could have gone back to her own people, but she feared Naomi might starve or come to harm. So, in the face of danger, she stays regardless of consequences. She stays out of love.

In a patriarchal time, they have no husbands and no sons. They have no one to legally or culturally represent or protect them. They have no formal social safety net, but they do have the law of the Lord which calls for the people to love widows, orphans, and aliens. They have allowances for gleaning fileds to help care for for those in need. On top of that, the Mosaic code calls for a Redeemer (a Goel). A Redeemer is a person who, as the nearest relative of someone, is charged with the duty of restoring that person’s rights and avenging wrongs done to him or her. This duty and eventual love of Boaz, a faithful and observant Jew, becomes a mechanism for Ruth’s formal adoption into the people of Israel. It happens as he comes to see the inner beauty, love, and faithfulness of Ruth underneath any family or tribal name.

As I said, this story was likely written down upon the return of the exiled community. They came back to a land where only a small, faithful remnant remained, and Jewish women and men had come to marry into other tribes. It was a hot button issue of sorts at the time. In addressing this historic reality, A Jewish resource states, “Rabbis use her story to show that true ‘Jewishness’ is judged not by ancestry, but by acceptance of God and the mitzvot [commands of the Torah]. Indeed, it is from this convert’s line,” they teach, “that the savior of the Jewish people must be born.”[iii]

One might say that she was saved by grace through faith in the one true God, the faith of Abraham, and we as Christians believe that the ultimate Savior, Jesus has come. You should remember that as time unfolds, Ruth becomes the great-grandmother of King David and ultimately an ancestor of Jesus. Yes, even Jesus was not purely Jewish. (How appropriate for a person who has come to save the entire world, regardless of tribe or family status.)

For Jewish believers and Christians alike, Ruth is a model of steadfast love and mercy. In Hebrew, this is called hesed. It is loving kindness often offered to those who do not deserve it. It is love for love’s sake, As we wrestle with our anger or fear, as we face evil in the world or the hearts of others, perhaps we should seek to remember Ruth’s story. It challenges us not to sin in our anger, or exact revenge instead of justice, or ignore the suffering even of our enemies. For God hopes they will become part of out family, too. One seminary professor writes, “Like many other Old and New Testament passages (Exodus 4, Joshua 2, 2 Samuel 11, Acts 10:34-5, Romans 2:14-5), [the Book of Ruth] shows us that loyalty and faithfulness includes us among God’s people, not biology, genetics, culture, or history.”[iv] For whether we want it or not, always like it or not, God is calling us to ultimately live like family with one another.

So, tough love might sometimes be needed. Separation for a time for the sake of safety might be required in certain circumstances. Consequences, justice, or even war come to pass as needed. Yet, empathy, compassion, and love – no matter if one deserves it or not – always remains our ultimate call from God. Hesed should inform any action.

Yes, I know that we all will struggle with this as a fallen humanity prone to sin and holding grudges. True, we might never clearly see such an idyllic world come to pass in our lifetime. And still, God invites us to join in his holy efforts. Christ wills to draw all people to himself. The Holy Spirit ferments communion and seeks to transform the heart of everyone in love.

Whether others do or not, we are asked to strive to make hesed a reality and our ethical norm for all our actions…to seek to live like Naomi and Ruth. No matter how hopeless it sometimes seems; we are asked to hope in and live for God. For this is God’s will, and someday it will come to passs. Amen.

[i] Although still debated, for just one such study as an example, visit: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2566511/#:~:text=Whereas%20our%20findings%20show%20that,Caucasian%20infants%20display%20a%20novelty.

[ii] Find it here: https://lutheranworld.org/news/israel-and-palestine-civilians-must-be-protected-and-hostages-released?fbclid=IwAR14oZVrD0dJeCv0s85URHIL0oPE7Uj36PadcsO4LPC-c2zEVGwtw1Ij2z8

[iii] See the entry for “Ruth” in the Jewish Virtual Library at https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/ruth

[iv] See https://www.workingpreacher.org/commentaries/narrative-lectionary/ruth-3/commentary-on-ruth-11-17-3