Another Reformation Day is upon us, and so one might wish to ask in the spirit of Martin Luther’s Small Catechism, “What does this mean?”

Reformation Day is a church festival that recalls how the Holy Spirit moved through Martin Luther and other Reformers to spur a religious, political, and cultural reform movement that reshaped modern history and had many lasting effects.

Many mark the feast through worship on the Sunday prior to October 31st calling it Reformation Sunday. Because we believe it was Spirit led, the liturgical color of the day is red recalling the fires of Pentecost. In 1517 on All Hallows Eve (All Saints Eve today), professor and monk, Martin Luther, posted his 95 Theses in Wittenberg, Germany, listing points of debate and inquiry regarding the practice of indulgences by the Medieval Roman Catholic Church and its associated abuses. It sparked a fire leading to a reexamination of all Medieval church practices in the West, and as a result, some unintended fractures came to pass. Yet, it also bore the fruit of a purified theology in a Church seeking to resist superstition, ignorance, and abuse. Biblical scholarship of today originates with the Reformation witnesses, especially Martin Luther.

Although others before Luther had suggested sharing the scriptures and worship in the common, local tongue, it stuck as a widely accepted norm after Martin Luther’s efforts to translate the Bible into German. Where the Medieval church had stopped allowing laity to share the blood of Christ (the reason is lost to us), the Reformation emphasized a return to Christ’s teaching that the body and blood be shared among all baptized believers. The spiritual equality of laity and ordained person as one within a “priesthood of all believers” became a force in the daily life of the Church, and with that, laws, schools, and governments saw reforms helping to lead Western Europe out of the dark ages. Everything was on the table for review, such as what books should be considered scripture or what of the seven major ministry practices of the Church should be considered sacrament. (Martin Luther came to argue that only baptism and the Eucharist were sacraments, although confession was held up as a sacrament in his earlier catechisms.) Perhaps the biggest change was understanding that we are saved by grace through faith in Jesus Christ, not by any works on our part.

Certainly, this is a broad brushstroke, as there remained many voices arguing over theological nuances and details right up through today. Even among those Christians coming to be known as Lutherans, there were arguments. Philip Melanchthon, a coworker with Luther who is largely responsible for the famous Augsburg Confession defending the Reformers’ faith, was even blacklisted by some for his attempts to reconcile with followers of John Calvin. Later, Lutherans would divide over local or national practices, how strictly one should adhere to the Lutheran confessions (the central writings of the Lutheran faith), as well as how “orthodox” (traditional, usually more high Church) worship should be or Pietistic (heart centered, often low Church). Luther himself has rightly come under some criticism for his support of government suppression of the German Peasant Wars, his approval of the persecution of Anabaptists, and later in life, his hardening heart against his Jewish neighbors. (These issues merit a separate essay of their own.) Luther like all of us is a sinner-saint at best.

Yet, Lutheran witnesses would positively influence the larger Church and world too. The Lutheran pastor, Martin Bucer, influenced Anglican worship and the formation of the Book of Common Prayer. William Tyndale who is credited with creating the first English biblical translation that was mass-produced studied in Wittenberg. The Thirty-Nine Articles, the historically defining statements of doctrines and practices of the Church of England, largely reflect the arguments of the Augsburg Confession. The oppressed Moravian Church was saved by a Lutheran, and they now adhere to Martin Luther’s Catechism. (They are one of six denominations with which the ELCA shares full communion.) They, in turn, introduced John Wesley to Luther’s Commentary on Romans which “strangely warmed his heart” resulting in what we now know as Methodism. A Lutheran helped influence the foundation of Alcoholics Anonymous, while another Lutheran helped form the Gideons. The Lutheran understanding of justification by faith has now led to The Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification (JDDJ) signed by the Lutheran World Federation and the Roman Catholic Church on October 31, 1999. Twenty-five years later, the World Methodist Council, the Anglican Communion, and the World Communion of Reformed Churches have also signed. (There are still some issues with details and practice, but we formally agree that only God’s grace can save us.) Even our Roman Catholic siblings have adopted many of our 16th Century Reforms after their council gathering now known as Vatican Council II (in the 1950s). Lutherans have also been center stage when it comes to relief efforts and work with Refugees. In fact, one in five Americans receive assistance through Lutheran ministries/nonprofits under the banner of Lutheran Services in America, one of the nation’s largest and most respected health and human services networks.

The impact of the Reformation is still being worked out in our lifetimes. It has faced many bumps in the road, we can fall short, but God is still at work. On Reformation Day, it is ultimately God who we celebrate. You might like to explore some of these resources to learn more:

By Heart: A conversation with Martin Luther’s Small Catechism was written by one of my former professors, Dr. Kirsi Stjerna, and several others. It is an excellent, accessible, highly readable unpacking of Lutheran core beliefs.

The ELCA publisher Augsburg Fortress points out, “Martin Luther posted his Ninety-five Theses on the church door at Wittenberg in 1517. In the three years that followed, Luther clarified and defended his position in numerous writings. Chief among these are the three treatises written in 1520.” They still apply today, and you can find them in one text at the Augsburg Fortress website, Amazon, or through other vendors. His Three Treatises (“To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation” asking leaders to play a part in the Reformation; “On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church” particularly focusing on the Sacraments; and “On the Freedom of the Christian” about living the Christian life) are fundamental to understanding the Reformation. As a former Roman Catholic, I can testify that they still have application in our times.

You might also like Heiko Oberman’s Luther: Man Between God and the Devil, a deep, psychological and spiritual treatment of Luther.

The Annotated Luther Series illuminates the essential writings of Martin Luther. You can find it here: Annotated Luther Series.

If you want to go all in, Logos.com offers the collection of Luther’s writings (55 volumes) for online access at $259. Since this collection was created, several more volumes have been added as his works were translated from German. Those are available at an extra charge.

Lutherans solidified their faith by agreeing on core documents collected now in our book of confessions called The Book of Concord, meaning book of unity. You can see it for free online at several sites, or buy it at Augsburg Fortress or another vendor of your choice.

If you prefer podcasts, try the Doth Protest Podcast. It focuses on church history and how the theology of the 16th-century Reformers can inform us today. Many Lutheran scholars are interviewed among others from varied traditions. A friend of mine, a local Episcopal priest, is one of the hosts.

For heavier theology, you might enjoy the Queen of the Sciences Podcast: Conversations between a Theologian and Her Dad. Rev. Dr. Sarah Hinlicky Wilson is Associate Pastor at Tokyo Lutheran Church and the Founder of Thornbush Press. Her father is Paul Hinlicky who after 22 years of service has retired from Roanoke College as the Tise Professor of Lutheran Theology. He is currently Distinguished Fellow and Research Professor of the Institute of Lutheran Theology.

Then, of course, there are many movies about the Reformation. Luther (2003) is among the most recent starring Joseph Fiennes, Bruno Ganze, and Peter Ustinov. You can find many past documentaries streaming as well.

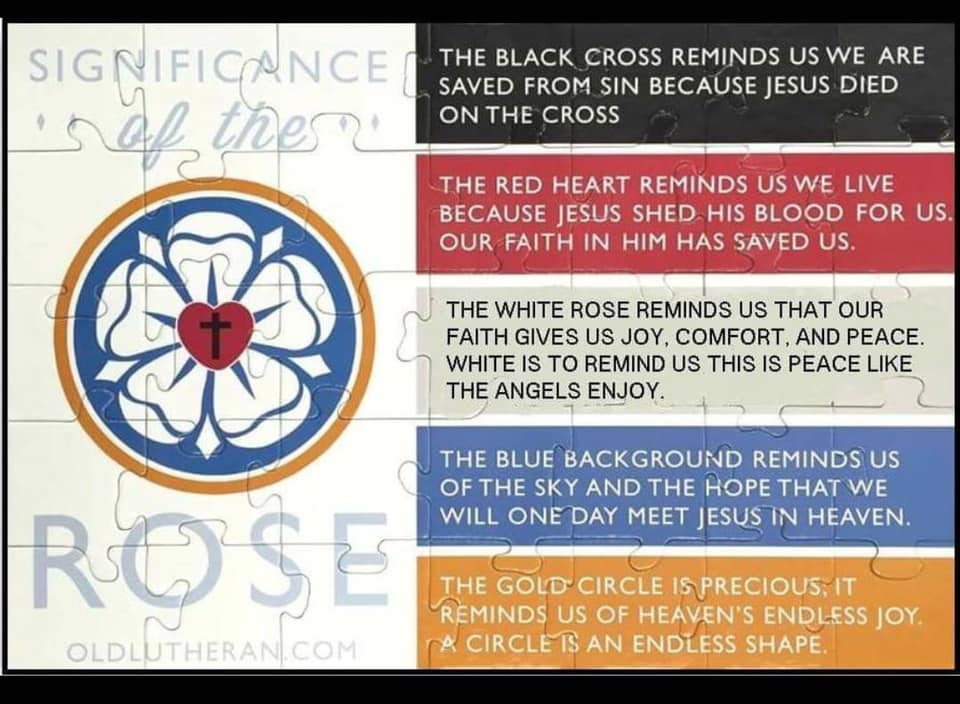

Have you ever seen the rose image on the floor in our Christ Lutheran entryway? The Luther rose or Luther seal is a widely recognized symbol for Lutheranism. It is the seal that was designed by Martin Luther while Luther was staying at the Coburg Fortress during the Diet of Augsburg. Martin Luther thought it a summary of our Lutheran faith. See the image below for an explanation. (Source: OldLutheran.com)

Originally published in the October 22, 2024 weekly newsletter, the Hub, of Christ Lutheran Church, Fredericksburg, VA.

© 2024 The Rev. Louis Florio. All content not held under another’s copyright may not be used without permission of the author.